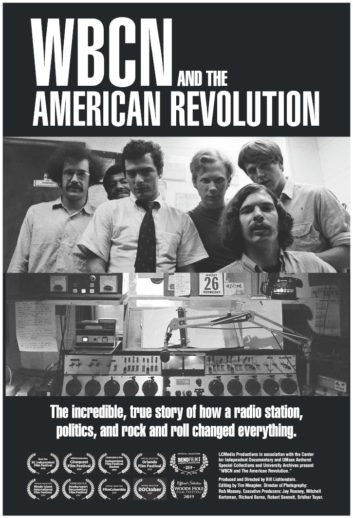

Bill Lichtenstein discussed the documentary and accompanying book, WBCN and The American Revolution on the Jan. 22 edition of Greasy Tracks.

Check out the archive by clicking here, while a playlist is here.

A Peabody Award-winner, Bill Lichtenstein — who produced and directed the documentary about the legendary Boston FM radio station — began working at WBCN at the age of 14 in 1970 answering the station’s “listener line” and later did newscasts as well as hosting programs.

Considered one of the first underground/progressive rock stations in the country, WBCN’s roots can be traced to 1958 and Concert Network Inc., which was owned by engineering wiz T. Mitchell Hastings who had a handful of FM stations in his portfolio. WBCN’s call sign stood for “Boston Concert Network” and sister stations included WHCN in Hartford, WNCN in New York City, WXCN in Providence and WRCN on Long Island.

FM radio was still experiencing growing pains in the 1960s and within a decade of going on air, Hastings’ stations were all in financial distress, most on the brink of going out of business.

Enter Ray Riepen, a lawyer from Kansas City, who two years earlier came to Harvard Business School to get his master’s degree. By the start of 1967, Riepen and David Hahn founded The Boston Tea Party, a music venue in Boston’s South End. The building had been a place where underground films were shown, but was built in 1872 as a synagogue before becoming a Unitarian meeting house/street mission.

At the onset, the Tea Party presented local acts, but in time, would have national and international bands that would go on to become household names. The Who, Led Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac, Cream and Pink Floyd among many others would list the important role the Tea Party made as far as getting a crucial foothold in the important U.S. market.

Along with The Fillmore in San Francisco and The Grande Ballroom in Detroit, the Tea Party became a sought-after destination for scores of bands, many who would play the venue multiple times.

By 1968, Riepen had experienced firsthand the audience/market in the metro-Boston area based on the success of the Tea Party and approached Hastings and convinced him to let him program the overnight hours at the failing station.

Opting to steer clear of “professional” radio announcers, Riepen put together a bunch of college disc jockeys and hippies from the local community to be the air staff. Hastings eventually made Riepen general manager. On March 15, 1968, as Cream’s “I Feel Free” hit the airwaves, WBCN was no longer a classical music station, instead going into freeform mode airing everything from non-Top 40 rock and jazz to blues and soul music depending on the mood of any of the eclectic hosts when they were on air.

Essentially it was a case of expect the unexpected at WBCN.

After the format change, ad sales steadily grew, but the station staff would have the final say on what ads were aired and many times produced spots for local businesses. For many years, ‘BCN steered clear of advertising for national brands, etc. As FM rock stations began to become more commonplace across the country, most tried to replicate WBCN.

Musicians quickly learned about the upstart station because Riepen made it possible to broadcast remotely from backstage at the Tea Party. Musicians playing dates in Boston would regularly show up at WBCN after concerts, many times staying in the studio for hours.

The documentary, which came out in 2019, and the recently published book on MIT Press, focus solely on the station during the 1968-1974 era — a period, according to Lichtenstein, when WBCN was the “internet of its time” and was a lightning rod when it came to activism against the war in Vietnam.

Less than six years after he arrived at Harvard, Riepen had sold his interest in WBCN, the Tea Party and the Cambridge Phoenix, a weekly counterculture newspaper. Riepen then left town and wouldn’t return to Boston for nearly 40 years when he came back to be interviewed for the documentary.

Lichtenstein captures the extent of Riepen’s long-lasting impact on the metro-Boston area even though his involvement in his business endeavors where relatively short-lived in the grand scheme of things.

Over the years, WBCN played a major role breaking bands such as Aerosmith, The Cars, Boston and the J. Geils Band — future Geils vocalist Peter Wolf was once an overnight host — and literally introducing U2 to the U.S. airwaves.

Just as media would change over time, so did WBCN. Stylistic changes, from airing Howard Stern to carrying New England Patriots game, also abounded. In 2009, WBCN’s corporate parent CBS Radio called time on the station’s incredible 41-year run by shutting it down.

The final track aired before WBCN became all-sports WBMX in 2009 was Pink Floyd’s “Shine On You Crazy Diamond.”